Quantum Ghost Imaging: Creating Images Through Quantum Correlations

What Is Ghost Imaging?

Quantum ghost imaging is a counterintuitive technique that uses spatially entangled photon pairs to create images of objects without the imaging detector ever directly seeing them. One photon from an entangled pair interacts with the object and hits a simple “bucket” detector, while its partner goes to a CCD camera that never sees the object. By correlating measurements from both detectors, an image emerges from the quantum correlations—creating a “ghost” image of something one detector never observed.

Overview and Results

This project was completed during my time in the quantum lab at my university. I worked together with a friend of mine, which is why I refer to “we” throughout this report. We drew inspiration from this Nature paper on quantum ghost imaging.

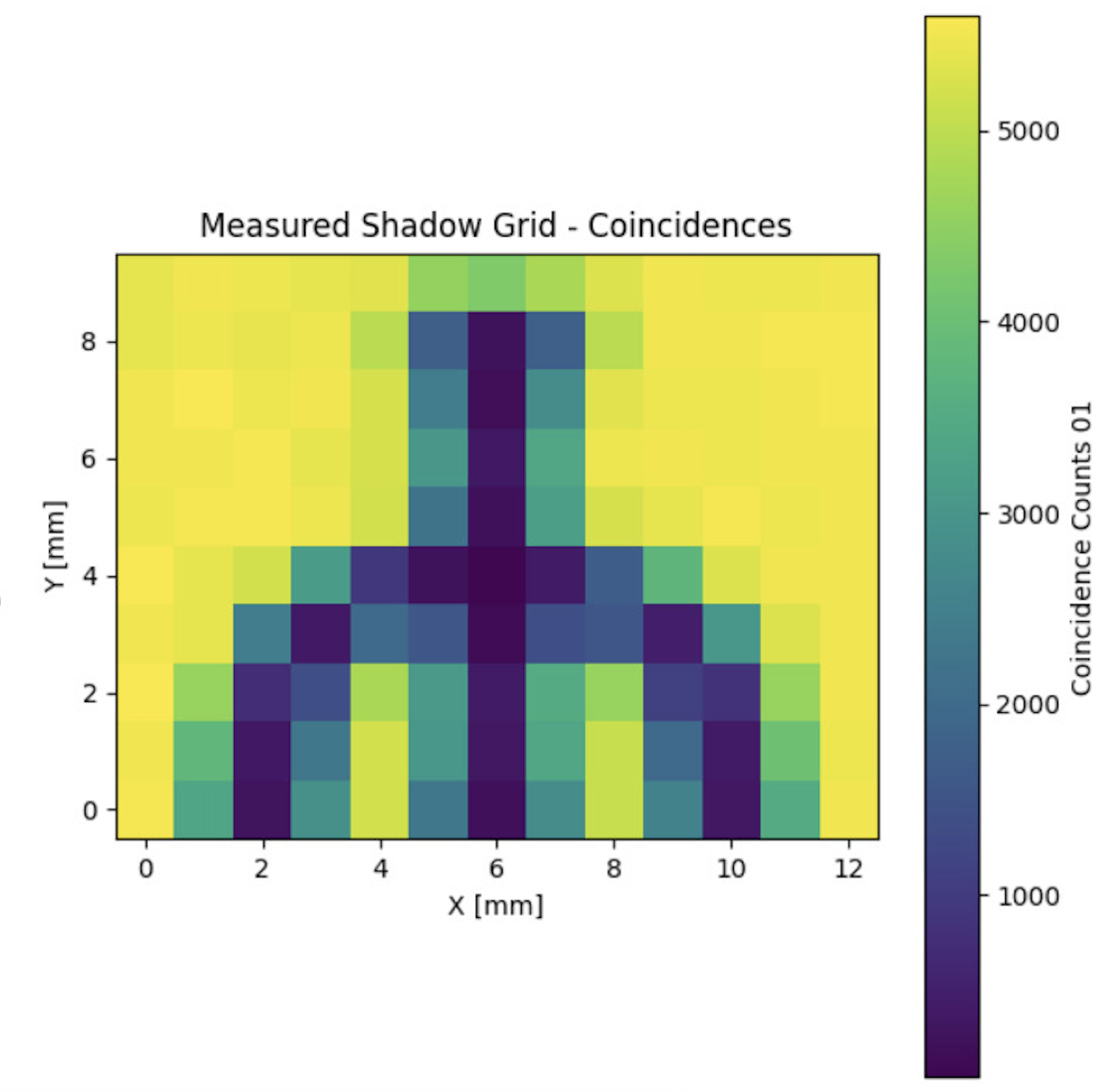

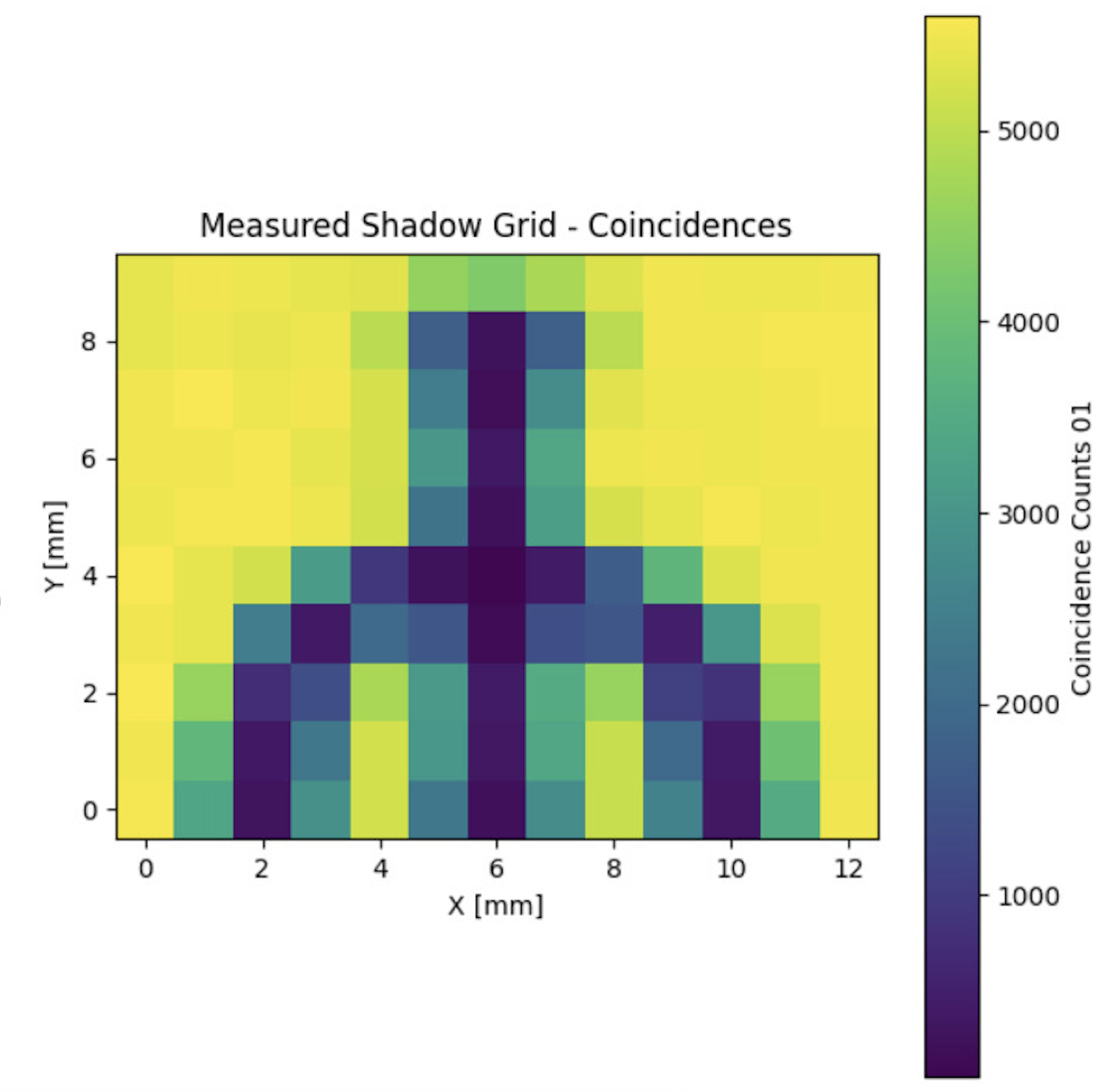

Despite working with limited equipment and a 10×13 pixel resolution, we successfully reconstructed clear images of two test objects: the letter “T” and the Greek letter “ψ” (psi), both of which are easily recognizable in the final ghost images. This demonstrates that the quantum correlation principle works even with significant experimental constraints.

Result of the Quantum Ghost image we took from a 3D-printed Psi

Detailed Explanation of the Experiment

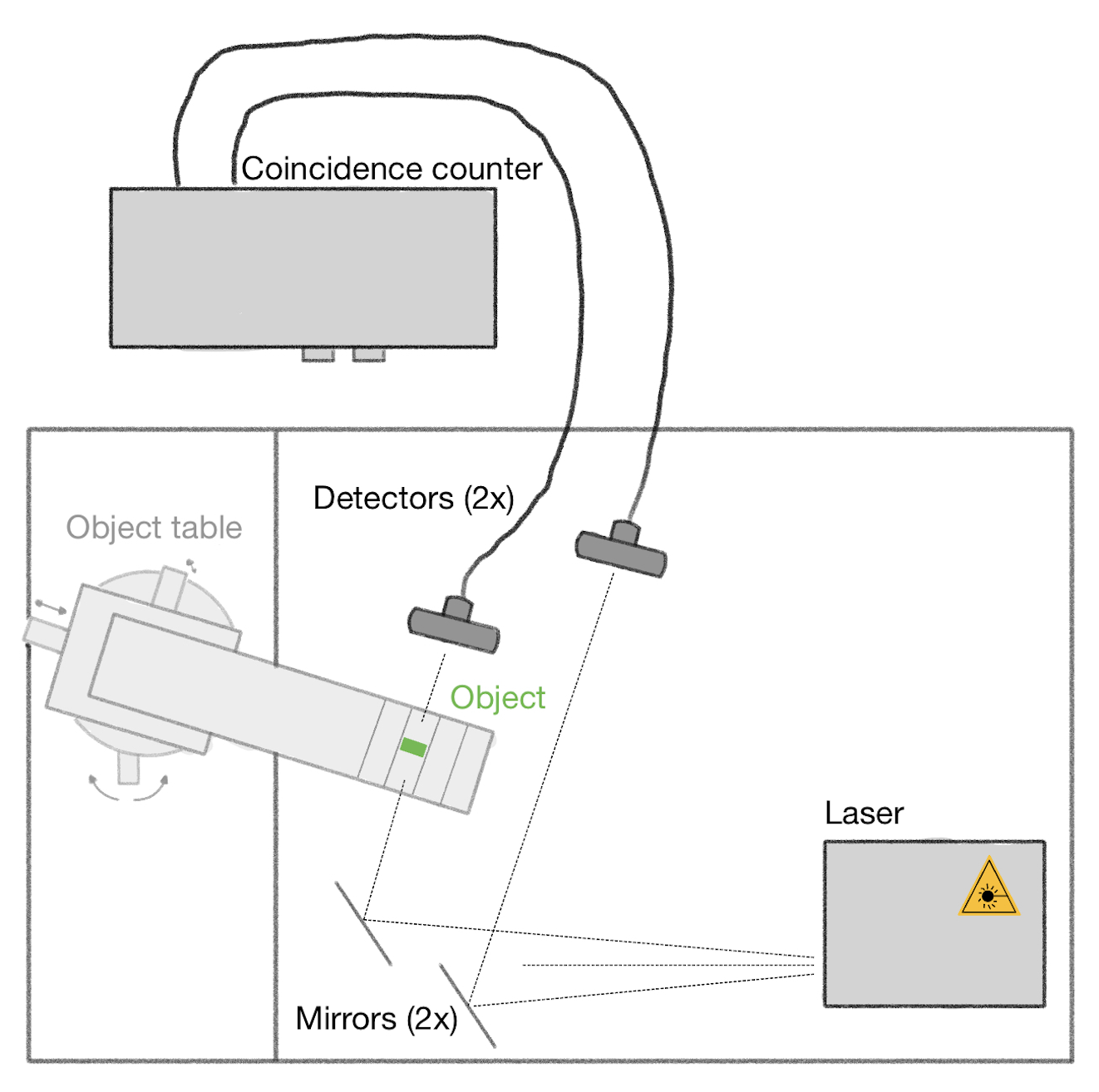

Building the Setup

Our original plan called for spatially entangled photon pairs, but we had to work with the equipment available in our lab. Instead, we used the quED (Quantum Entanglement Demonstrator) system that generates polarized entangled photon pairs. This meant developing a workaround that still demonstrated the core ghost imaging principle, even though it wasn’t the textbook implementation.

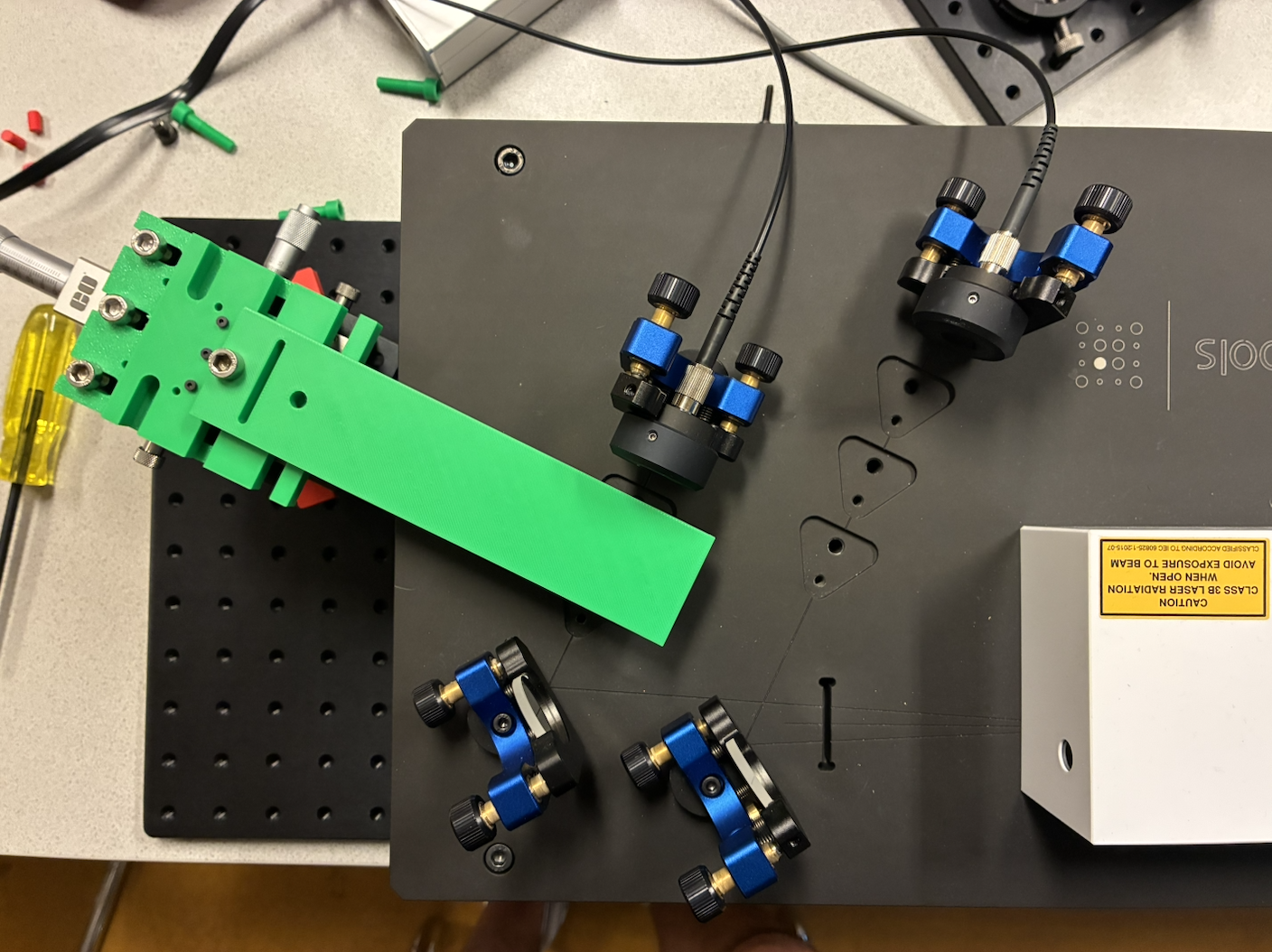

Ghost imaging requires precise positioning to scan objects through a pixel grid, which created significant mechanical challenges since each pixel needed sub-millimeter accuracy for meaningful data collection. We initially tried to automate the process using existing stepper motors from our polarizer setup. However, our 3D-printed linear stages had too much mechanical play for the precision required. The gear ratios needed for higher accuracy couldn’t be achieved with our available filament thickness, so we switched to manual positioning using lab-grade optomechanical components.

Sketch of the setup (left) and Final Setup (right)

Components:

- quED Entanglement Demonstrator: Source of polarized entangled photon pairs

- Adjustable Object Table: Manual positioning system with Y and Z-axis control

- Coincidence Counter: Electronics to correlate detection events between both optical paths

- Dual Detection System: Bucket detector for the object path, position-sensitive detector for the reference path

- Optical Components: Mirrors and beam splitters to direct photons along their respective paths

Taking Ghost Images

We limited ourselves to 10×13 pixel images due to the manual data collection. This resolution was determined by the detector lens geometry and represented a practical compromise between image quality and the time required for manual data acquisition. We 3D-printed test objects specifically designed for our experimental constraints, featuring simple geometries with straight edges to maximize contrast within our limited pixel resolution. We chose the letter “T” for its simple, recognizable shape and the Greek letter “ψ” following examples from the literature that inspired our project.

The experimental process required careful attention to detail. We spent considerable time finding the optimal object height through trial and error, as this critically affected signal visibility. For each of the 130 pixel positions, we manually adjusted the Y-and Z-position, recorded coincidence counts and documented the measurements. While time-consuming, this manual approach allowed us to maintain quality control throughout the data collection process.

Results and Discussion

Both test objects are clearly visible in the reconstructed ghost images. The “T” and “ψ” are easily recognizable, confirming that we successfully implemented quantum-correlated indirect imaging despite our experimental limitations. An important aspect of our setup was the ability to compare ghost imaging results with direct single-detector measurements. This comparison revealed that while our polarized entanglement approach successfully demonstrated the ghost imaging concept, it didn’t provide the signal-to-noise advantages typically associated with spatially entangled quantum systems.

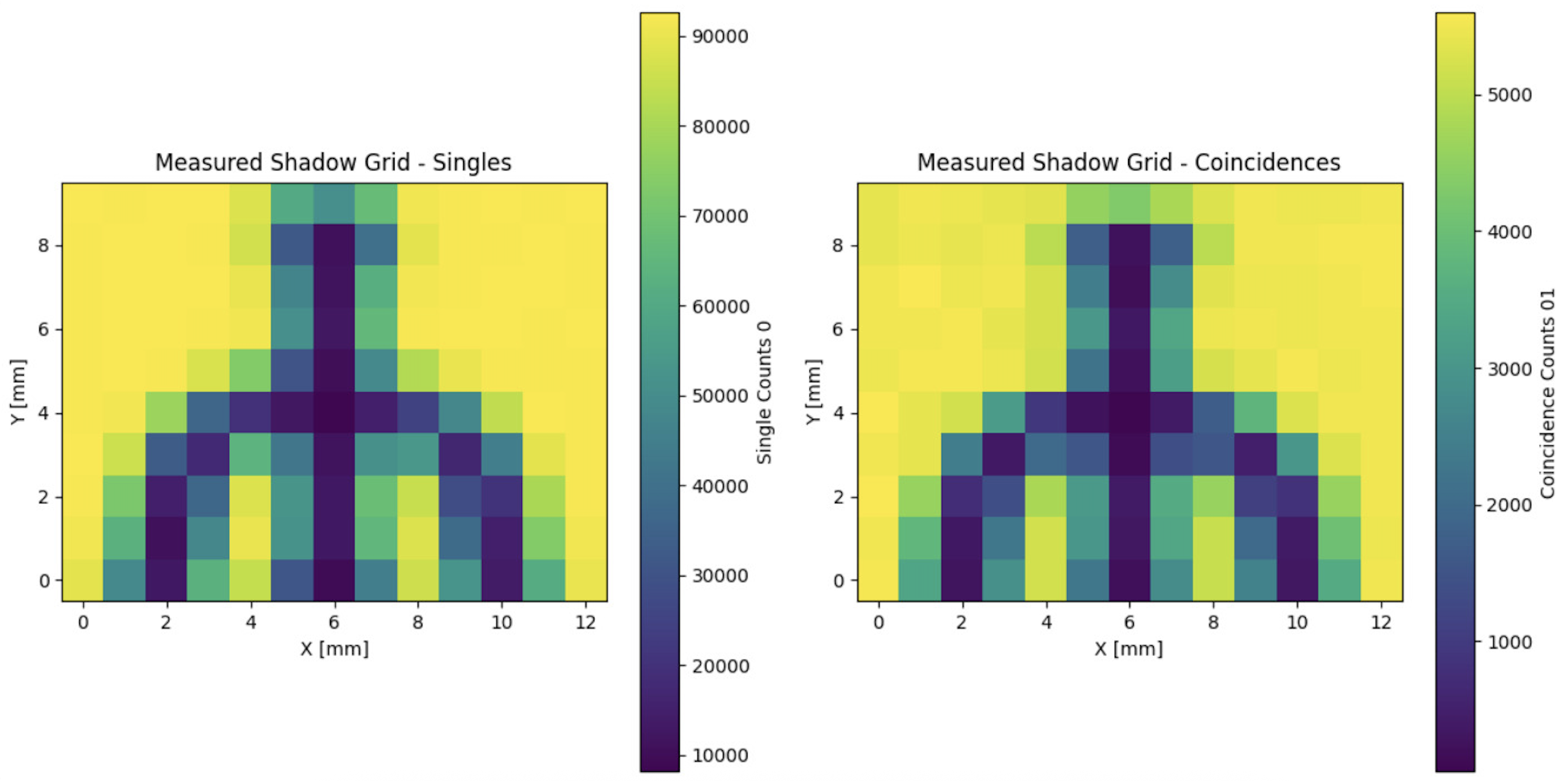

Entangled Counts (left) vs Entangled Counts (right)

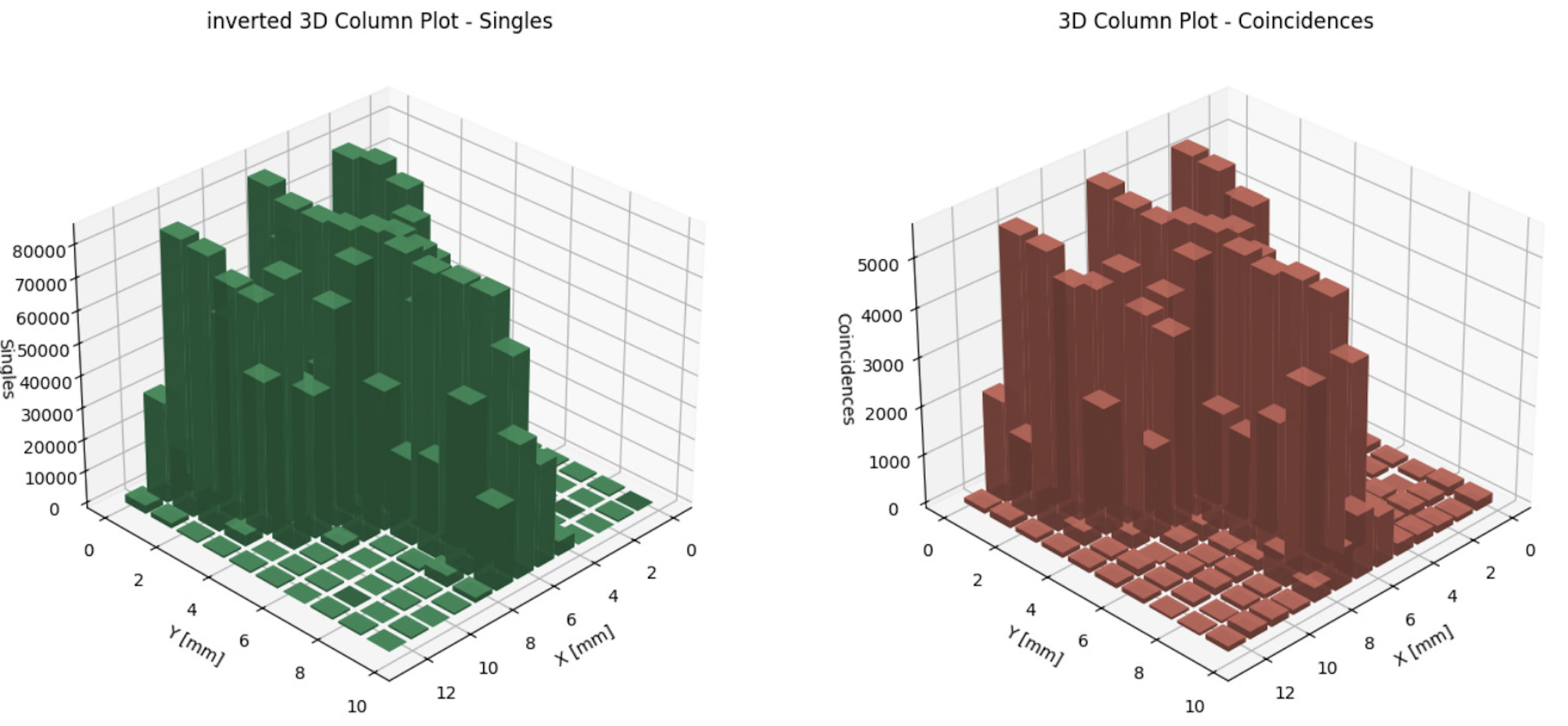

Same Results displayed as a 3D-Column Plot

Conclusions

Overall, this project successfully demonstrated the fundamental principles of quantum ghost imaging within significant practical constraints. While our implementation differed from ideal textbook setups, the clear visibility of both test objects validates the core concept of quantum-correlated imaging.

The project highlighted the reality of experimental physics: adapting theoretical concepts to available equipment often requires creative problem-solving. Working within our constraints rather than being limited by them provided valuable insights into both the fundamental physics and practical engineering aspects of quantum imaging systems. The experience reinforced that successful experimental work often depends as much on resourcefulness and adaptation as on following established protocols.

Key Takeaways

- Quantum ghost imaging can work even with non-ideal entanglement sources

- Manual precision positioning can substitute for automated systems when necessary

- Limited resolution doesn’t prevent successful demonstration of quantum principles

- Experimental adaptability is crucial for laboratory success

This project demonstrates that meaningful quantum optics experiments are possible even with equipment limitations, providing a foundation for future work with more sophisticated quantum imaging systems.

Technologies Used

- Quantum Optics

- Entangled Photons

- Mechanical Engineering

- Python Data Analysis

- 3D Printing